This fall Seattle voters could approve new taxes to pay for bus service — and still lose their bus route. It sounds crazy, but if some activists get their way, Seattle bus riders will still see a shrinking system no matter how much money they pour into the system.

As Seattle debates which revenue source is the most progressive, a parallel debate is unfolding that pits progressive solutions against regressive cuts. Those cuts, justified by the ideology of austerity and sold in the language of efficiency, would scale back bus service even further, leaving only a privileged few with the chance to leave their car at home and ride an affordable, sustainable bus to work or to school.

At the press conference announcing the proposed head tax and commercial parking tax, Nick Licata hinted at this debate–and suggested it be deferrred until after the revenues were approved:

In many cases, the routes on Metro’s cut list have the lowest ridership–but may be the only transit at a particular time or to a particular neighborhood. If Seattle approves more tax, council members may buy service for routes where buses overflow, or stave off Metro’s cuts to less-used routes, or a mix.

Licata said route choices should be debated later, after the city approves money to protect bus riders.

This is the wrong approach. Now is the time to make sure that whatever revenue plan is adopted ensures that its spending is progressive, not just its revenues. Otherwise voters may reject the proposed funding sources if they lack confidence that the revenues will be used to save their bus.

Sustainability Isn’t Always Efficient

Who would argue that there’s such a thing as good cuts to transit service? One such argument came from, of all places, Sightline Institute. Jennifer Langston wrote soon after Prop 1’s failure that there could be such things as good bus cuts:

Some proposed cuts may increase Metro’s operating efficiency by targeting poorly performing routes—the ones with high operating costs or low ridership or that duplicate nearby transit service. Some will be painful and leave people stranded. Some might do both at the same time.

So far, Metro and its supporters haven’t done a great job of distinguishing—at least in the public debate—between cuts to low-performing routes that arguably ought to be sacrificed or restructured for the greater good and cuts to well-functioning routes with high ridership that will be gutted or cut back solely for lack of money.

This is a very regressive line of thinking, rooted in right-wing frames that emphasize “efficiency” over universality. Langston, writing for a sustainability think tank, is embracing concepts that exist to undermine sustainability itself.

If we are going to build a carbon zero city, we need to reduce the single biggest source of CO₂ emissions in Seattle: from transportation. That means we need to get as many people as possible to ride transit.

To do that, there have be routes operating for people to hop on board. Some of those routes will be packed. Some won’t be. But we must have a system with the capacity and coverage to pick up as many people as possible when high gas prices, traffic, or guilt about burning up our planet cause even more people to ride.

The concept of “efficiency” — that the only bus routes worth funding are those with the highest ridership levels — means that transit service can never expand to meet potential or growing demand. It means the suburbs will never get better service, since there won’t be bus service available to generate the levels of ridership that those calling for “efficiency” insist on seeing before supporting such service.

This approach is especially damaging when considering the huge cuts to Metro service that will happen without new funding. Metro has estimated these cuts would leave 10 million riders a year stranded. That’s almost a 10% reduction in ridership — even with a series of restructures designed to mitigate the impact of the cuts in the name of efficiency.

Many of the routes Metro identifies as “low performing” are not actually low performing. It’s an accounting trick designed to determine which parts of the system lose limbs and which merely lose fingers. One of the routes deemed “low performing,” the 28, is a workhorse that routinely carries full buses from Crown Hill through central Fremont, and down the growing Dexter corridor to SLU and Downtown. But because some other routes have even higher ridership, the 28 was seen as expendable. That doesn’t mean it’s an inherently bad route. It just means the proposed cuts will significantly undermine our transit system at a time when we need it to grow.

But there’s a bigger point here. Sustainability advocates must utterly reject the idea that our bus system should be focused on efficiency. It’s a metric imposed on us by right-wingers who dislike transit and don’t want to pay for it. Conservatives seek “efficiency” in transit because they hope that it will lead to an elimination of public funding for transit. Conservative voters won’t ever support transit taxes because they believe it’s an inherently wasteful use of money that doesn’t benefit them. If transit systems operate with less costs, that savings doesn’t get plowed back into transit — it gets used by conservatives to justify cutting transit budgets or cutting taxes.

Sustainability advocates have to reject the “efficiency” game because it is played with dice that are loaded against us. We must instead emphasize a robust bus and rail network that gives everyone a chance to get out of their cars and save the planet by riding a bus. Losing bus routes and thus losing riders is a huge step backward not only for transit in Seattle, but for any hope that we can lead the way to a carbon zero region.

Rejecting False Choices In Maintaining a Bus Network

There’s a similar argument at work from some transit advocates who argue, following Jarrett Walker, that we have to sacrifice broad geographic coverage in order to improve the frequency of a few popular routes.

This robbing of Peter to give more service to Paul doesn’t make sense from the perspective of getting as many people as possible to ride the buses. Usually those who lose bus service are of lower income and live in neighborhoods without many other travel options. Those who gain bus service tend to be higher income and live in dense neighborhoods that do have other options.

Those who advocate for this strategy usually justify it by citing smaller operating budgets that force hard choices. The way out of that, of course, is to expand the available funding for transit. That’s the entire point behind Seattle going it alone to approve new funds for Metro buses, ensuring that the “frequency versus coverage” argument is a false choice. Seattle can and should have both, especially if the goal is to build a sustainable city by getting as many people as possible to ride transit.

Why Shrink the Voter Base?

Not only is maintaining a broad network the right thing to do from an environmental, social justice, and transit perspective — it’s also a political necessity. Prop 1 failed in those parts of King County that didn’t have good bus service. Even within Seattle, voters were less likely to vote yes on Prop 1 if their neighborhood had no or infrequent bus service. It doesn’t make sense to shrink the number of pro-transit voters by shrinking transit service. It’s hard to imagine Seattle voters supporting funding for a few high frequency bus routes that serve a few dense corridors.

We can look to Pierce County for an example of what happens when huge swaths of voters are cut off from bus service. Voters there had rejected a countywide funding plan to maintain the existing system. Pierce Transit then made huge cuts, emphasizing service in a few core urban routes. Yet voters within Tacoma still rejected a proposal to fund a smaller network. There is just no political support for the kind of restructures that some transit advocates like.

This is part of a broader problem of political economy. Whether it’s cuts to Social Security benefits, transit, or other public programs, you can usually find some technocrat who believes voters will be happy to give up services or benefits in order to make things more “efficient.” Yet Social Security cuts remain hugely unpopular with voters. And as we’ve seen, so do transit cuts.

Voters don’t support austerity-based restructures. There’s no evidence to suggest they care about “efficiency.” Voters routinely have shown they prefer progressive solutions that expand public services, rather than regressive service cuts that privilege some at the expense of others. If Seattle and Metro followed this path, public support for transit would erode. It’s not a pretty future.

So what does a solution to this look like?

Initiative 118, developed by Friends of Transit, offered a sensible solution to this issue with the following language. First, it defined what “Metro Service Cuts” were:

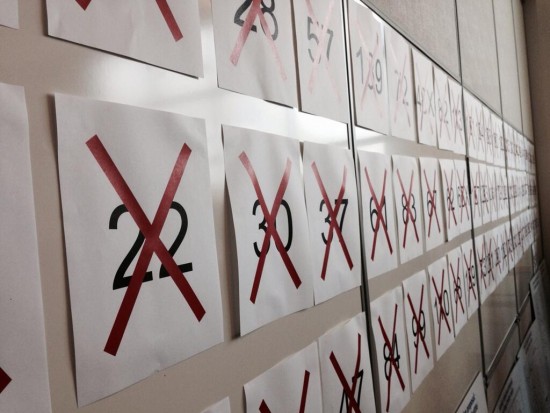

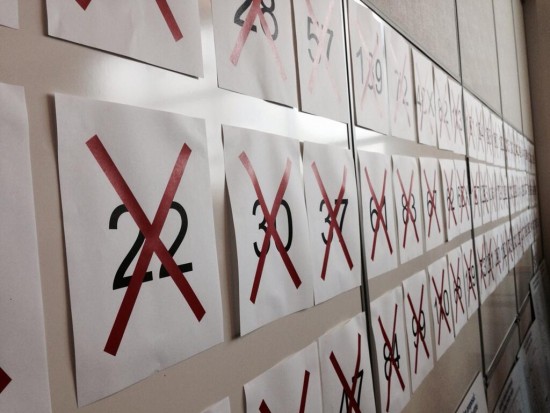

“Metro Service Cuts” refers to proposed reductions in service announced by Metro in November 2013 and April 2014, and any subsequent service reductions proposed to address Metro’s current projected funding shortfall;

And then it mandated that the funds were to be used to reverse those cuts:

100 percent to purchase service for Seattle Routes until Seattle Metro Service Cuts are restored

Initiative 118 also created a Public Oversight Committee to oversee the spending of these revenues. The initiative did not prevent Metro from finding sensible ways to improve bus service. But it was deliberately crafted to provide assurance to voters that their money would be use to save their bus routes.

We haven’t yet seen the language for Mayor Murray’s proposal, nor for the plan announced by Nick Licata and Kshama Sawant. But both ought to incorporate similarly strong language ensuring that Seattle’s existing bus routes will be restored. Seattle voters deserve to know that their money will be used to stop these cuts.

Those routes don’t have to last forever. Initiative 118 lasted only six years, a deliberate choice. 2021 is when North Link light rail opens to Northgate. That rail service will allow Metro to make big and positive changes to the bus route map in north Seattle. It’s also hoped that a lasting regional transit funding plan will be approved by that time.

Until then, it doesn’t make sense to slash any existing bus routes. With rising gas prices and rising sea levels, Seattle needs to make sure as many people as possible, no matter where in the city they live, have access to good transit. Doing so is essential to building a sustainable city.

The job of transit advocates is to work to expand the transit system and to aggressively seek the funding to pay for it. It’s time to abandon the flirtation with cuts and instead work to bring Seattle the robust and expansive transit system it deserves.

Robert Cruickshank

Robert Cruickshank is a transit rider and progressive campaigner who lives in Seattle’s Greenwood neighborhood. From 2011 to 2013 he served as Senior Communications Advisor to Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn.