Yesterday the Seattle City Council unanimously voted to pass the Bicycle Master Plan. This document largely covers the infrastructure that would be needed to build a complete network for safe cycling. It is neither perfect nor comprehensive but it does provide a vision.

The brief take on what this means is that the city is committing to a document for how cycling should be managed. In order to reach this conclusion it begins with five primary goals:

- Improve safety: The language of the document and the city council both understand the importance and scope of ensuring safe infrastructure for cycling. The plan makes a point of saying that facilities should be easy and safe to use for all ages and abilities. This could (and will likely) be measured by both the demographics of cyclists and fatalities/injuries of riders.

- Increase ridership: The plan also notes that achieving the other goals will likely increase ridership. Tracking ridership is a practical way of measuring the quality of cycling infrastructure but increasing ridership isn’t just a measurable outcome. Ridership also contributes to the other goals. There is research suggesting that increasing the number of cyclists may increase safety and definitely increases livability (both health outcomes and economic activity).

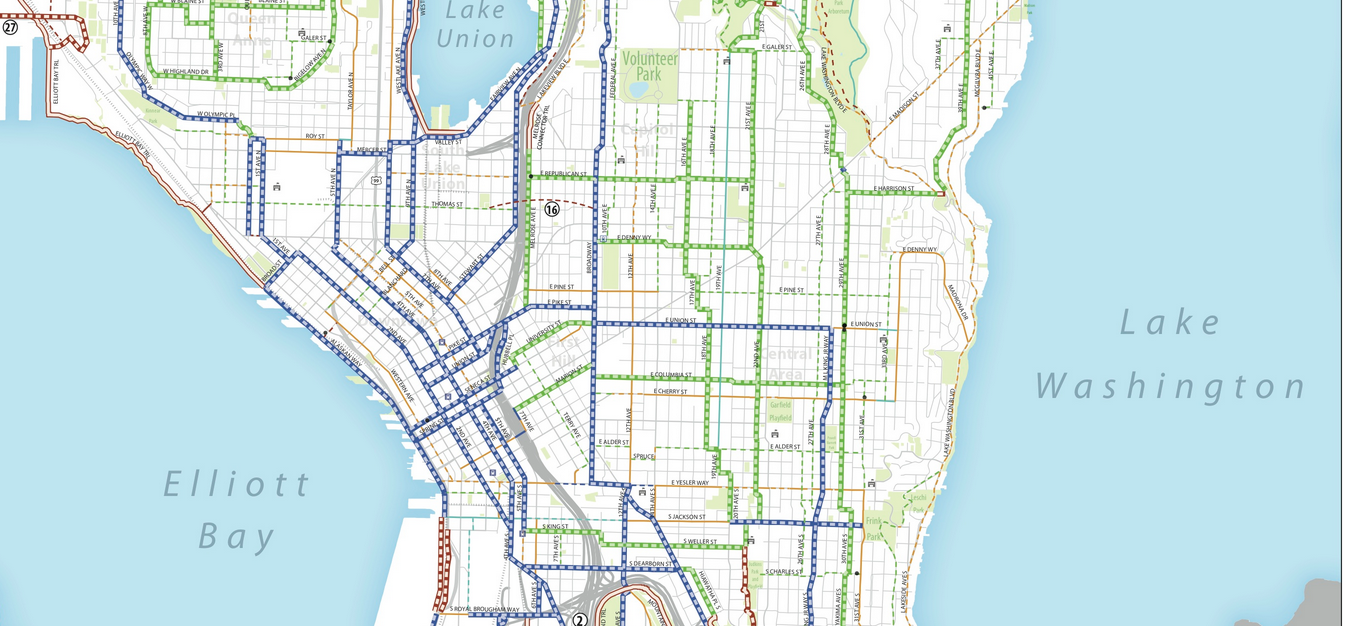

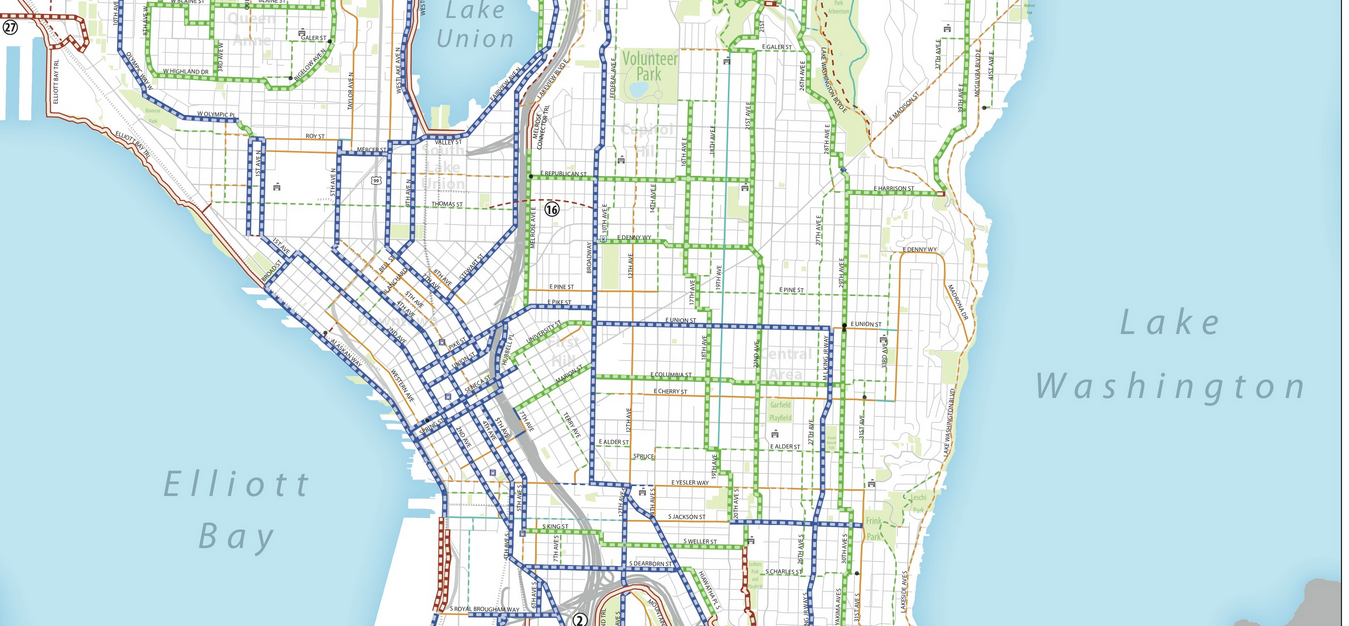

- Create connectivity: One of the biggest accomplishments of the plan is that it creates a vision for a network. The vision is specific and ambitious. A true bicycle network speaks to cyclists who are familiar with bike lanes that end abruptly or seem to lead nowhere. If you look at one thing from the plan check out the network.

- Provide equitable facilities: Like any grand project, bicycle infrastructure has the potential to positively affect every resident, whether they bike now, will bike in the future or won’t ever bike. The project will touch every neighborhood, require input and invest public funds. Unfortunately, we have a long history of under-investing in neighborhoods with less wealth and less power. For those reasons it’s important to explicitly state (and achieve) the goal of providing easy access for everyone to the facilities. Furthermore, there is a practical reason for spreading the infrastructure. This ensures neighborhoods see the benefits and have a stake in accomplishing the plan.

- Promote livability with a welcoming environment:This goal directly states the importance of cycling for healthy and vibrant neighborhoods. Building cycling facilities isn’t just for cyclist but to improve the dynamism of the entire city

Why The Plan Is Important

The plan is a pretty big document with a lot of details in it. Generally though, the actual document addresses a few different things:

- sets out what the goals are for cycling infrastructure

- gives a vision of what a cycling friendly city would look like

- standardizes a lot of the language and understanding for different cycling facilities

- creates a strategy for accomplishing the plan

Lastly, the plan has a purpose that’s not stated explicitly in the document, creating consensus. This may be the most important function of a master plan. The document has been developed over a long period of time with a lot of feedback. This serves to ensure the needs of our communities are understood and the goals are clear. There will be many controversial details to work through before the plan is achieved but the over-arching idea will serve to join communities and activists, even when the specific infrastructure they support isn’t in their neighborhood.

What’s Next

For the best summary of the most important next step, read about the funding issues covered on Seattle Bike Blog. The plan lays out infrastructure that may take as long as 20 years to build. Additionally, the unanimous vote by the council doesn’t actually dedicate any funding for any of the specific projects. It is likely that funding will have to be acquired for each and every project implemented. Perhaps the most important achievement to focus on next would be dedicating more money from the city’s general fund for cycling infrastructure.

Overall, it’s estimated that the city would need $20 million a year during the lifetime of the plan. While this may seem like a lot, it’s a fraction of what we spend on automobile infrastructure and large amount of it would come from sources outside of the city. Most importantly, the value of the lives saved and injuries avoided would well exceed this cost.

Owen Pickford

Owen is a solutions engineer for a software company. He has an amateur interest in urban policy, focusing on housing. His primary mode is a bicycle but isn't ashamed of riding down the hill and taking the bus back up. Feel free to tweet at him: @pickovven.