Seattle is set to embark on a major refresh of its housing and land use policy via the Comprehensive Plan due at year’s end, which has sparked plenty of debate. Critics worry that growing too fast and expanding denser multifamily zoning to single family areas will push out low-income residents and people of color. However, that analysis doesn’t align with history as reported in U.S. Census data.

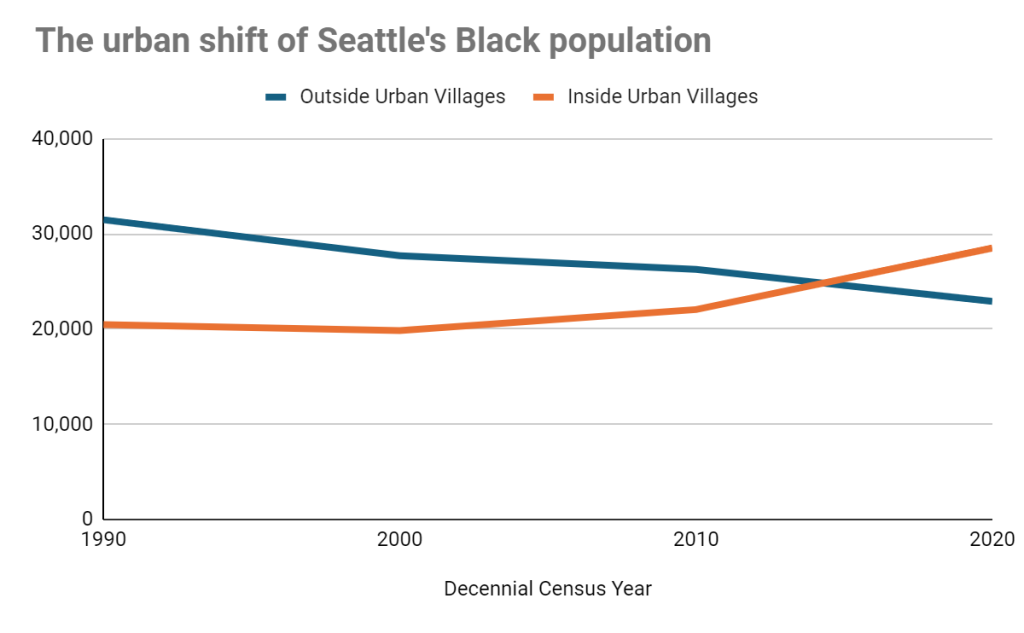

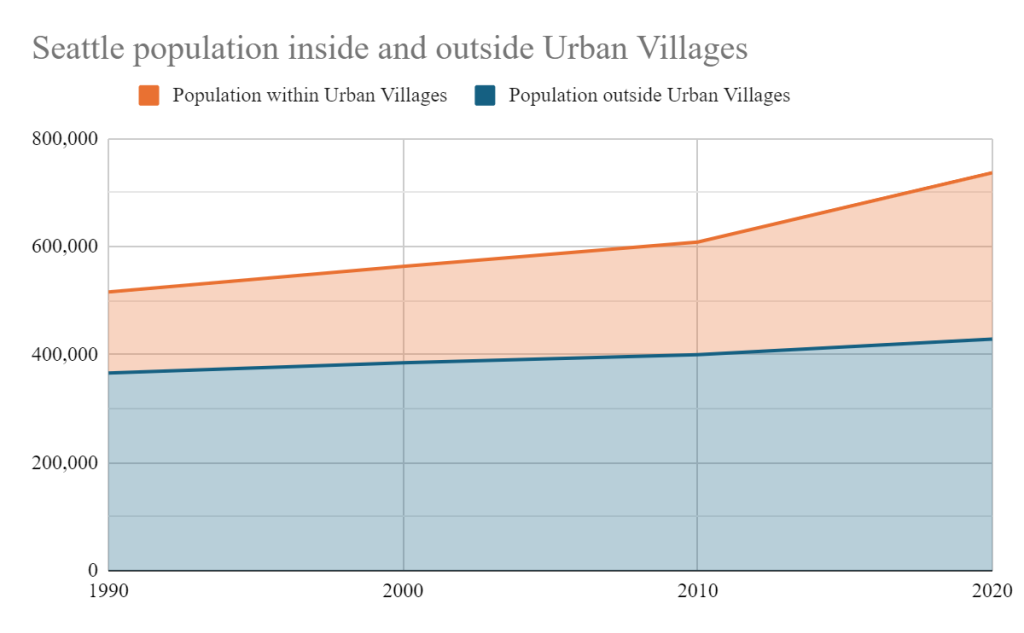

Between 1990 and 2020, Seattle’s single family neighborhoods saw their Black population decline by 8,575 residents according to Census figures. There is little reason to expect that trend to reverse if single family zoning continues to dominate those areas, driving up housing costs. Single family zoning consumes about two thirds of Seattle’s residential land, with little development occurring in those areas over that timespan. The population of single family neighborhoods grew just 9% between 1990 and 2020 even as Seattle as a whole grew 42%. In contrast, Seattle’s urban villages and centers more than doubled in population between 1990 and 2020.

Meanwhile, Seattle’s overall Black population was essentially flat citywide, decreasing slightly from 51,948 in 1990 to 51,419 in 2020. Thus, Seattle’s urban centers and villages (where multifamily zoning is prevalent) collectively saw an increase in Black population in order to maintain roughly the same Black population over that timespan, compensating for the drain of Black people from single family neighborhoods. Those designated growth areas added more than 8,000 Black residents over 1990 totals.

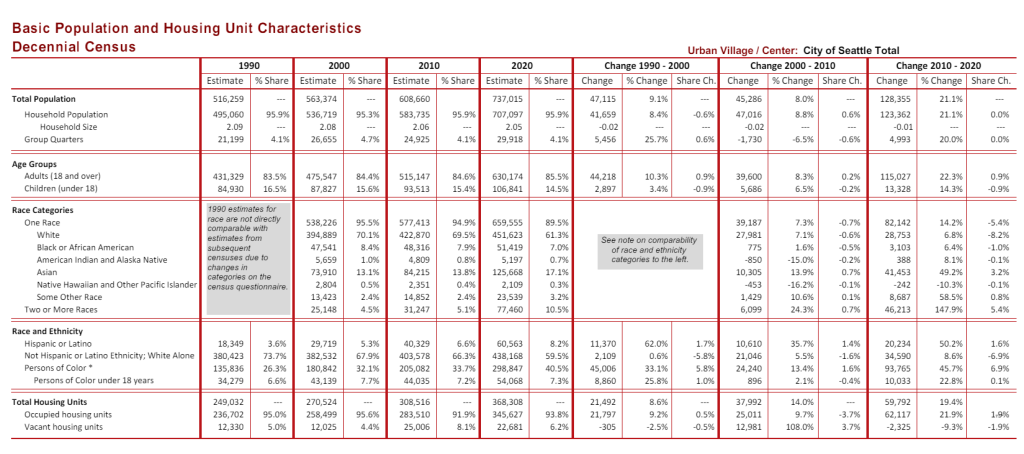

The Black population remaining flat while the city grew over those three decades led to the city decreasing from 10% Black to just 7% Black in that timeframe.

Where the Black population grew in Seattle’s urban centers and villages was not uniform, and a few urban villages, particularly in the Central District, lost Black residents at a significant rate despite the overall trend toward multifamily areas gaining Black residents. Meanwhile, Othello (in the Rainier Valley) led all urban villages and gained more than 2,184 Black residents since 2000. The Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) created a chart and data dashboard that lays out the trends by neighborhood for more information.

While the Black population share shrank, overall Seattle has grown more diverse since 1990. The Asian population doubled and reached 17% of the total population. Seattle’s Latino population more than doubled to 8%, with the caveat that the Census Bureau changed how they asked about Hispanic heritage in that timeframe, making the results not perfectly comparable. White people composed 75% of Seattle’s population in 1990, but 61% in 2020.

With trends showing single family zones are repelling Black people from Seattle, one might expect Mayor Bruce Harrell to be championing reforms to add more housing in these areas. After all, Harrell is half-Black and half-Japanese and often speaks about the need to overcome the legacy of racism, “lead with equity,” and embrace diversity. However, overhauling single family zoning in the name of racial equity is not the direction his administration has taken thus far, with final decisions fast approaching for the Comprehensive Plan major update.

In fact, public records first unearthed by The Urbanist revealed that Harrell’s team pushed to reduce housing options and keep some single family zoning in the draft Comprehensive Plan the City released in March. The revised version also de-emphasized the role of restrictive zoning in upholding exclusion and racism as compared to the earlier OPCD draft that did raise those issues.

Former Seattle City Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda took great pains to push OPCD to conduct a racial equity analysis of Seattle’s “urban village” growth strategy, which has been in place since 1994, ultimately relying on a budget proviso to force the analysis. While former Mayor Jenny Durkan repeatedly delayed its release, the report did ultimately show that restrictive zoning had hugely detrimental impacts and worsened racial disparities.

OPCD had sought to incorporate findings from that analysis into its draft Comprehensive Plan, before being hampered by Harrell’s policy team. PubliCola analyzed OPCD’s earlier version versus the Mayor’s version and found mention of new anti-displacement measures had been stripped out and discussion of racial equity watered down in general. Rather than owning past policy mistakes in creating a housing crisis, the revised plan stresses outside market pressures.

“But market pressures don’t exist in a vacuum, a now-deleted section of the draft plan reads. They are exacerbated by the preservation of ‘exclusionary zoning’ in whiter, wealthier single-family areas, which ‘limits access for lower-income people and contributes to displacement in other more vulnerable areas as people priced out of these neighborhoods look elsewhere for housing and bid up homes in relatively lower-cost areas’—not in some distant, racist past, but in our present, because of policies in place today,” PubliCola‘s Erica Barnett wrote. “These deleted sections, which span pages, weren’t just rhetoric; they directly informed city planners’ proposals for the policies they included in the early draft of the plan, including new tenant protections, more apartments all over the city, and ‘substantial’ increases in funding for existing and new anti-displacement strategies.”

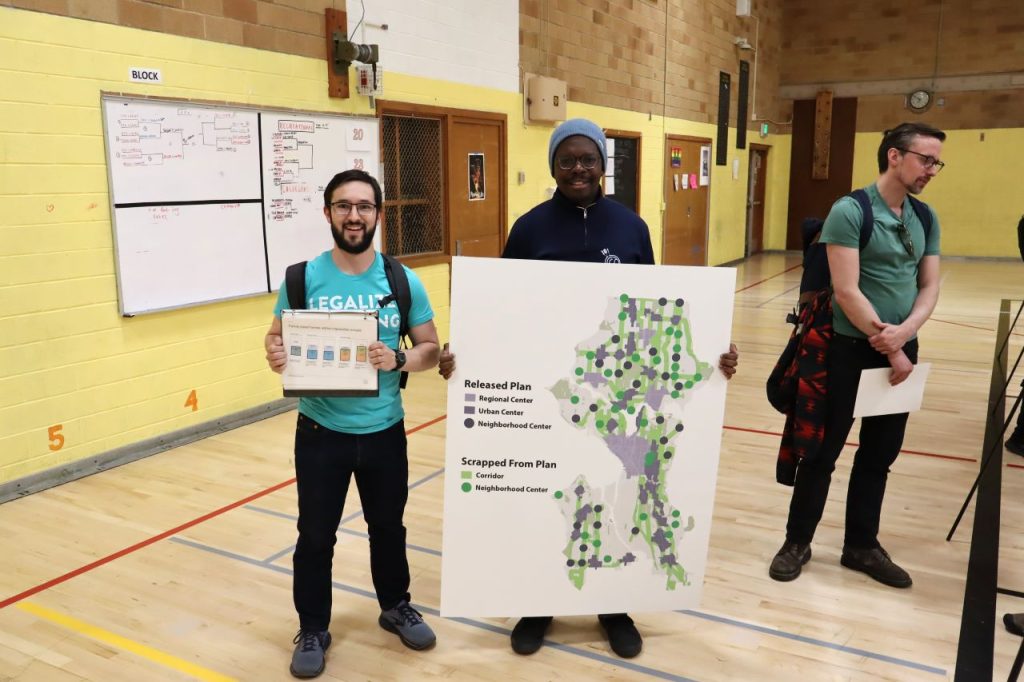

Harrell’s lackluster proposal has prompted housing advocates to push back, and many turned out at the open houses that OPCD hosted on the draft plan, including Seattle YIMBY’s Sanders Lauture. As The Urbanist previously reported, Lauture and other pro-housing activists argued OPCD’s earlier housing abundance map — which included nearly 50 larger neighborhood centers instead of 24 smaller ones and five-story “Corridor” zoning within an eighth-mile of frequent transit — better reflected what Seattle residents want.

“Especially with the draft plan that was released by The Urbanist and PubliCola from the public disclosure requests, you saw the OPCD actually was listening back in early 2023, that they had a plan that was ready, that addressed some of the concerns that people were having about housing affordability,” Lauture said. “And the mayor’s office removed a lot of the additional housing options that were available across the city.”

Housing advocates continue to make the case that the lack of housing options in Seattle is breaking up communities and contributing to displacement.

“Everyone wants more housing in their neighborhoods,” Lauture said. “They’re tired of housing prices going up. They want to have kids be able to live in the neighborhoods that they grew up in. They want to be able to have a family in an apartment that’s three [bedrooms] or more.”

In 2023, the Washington State Legislature passed a new minimum standard for fourplex zoning in large cities like Seattle, which goes into effect next year. Seattle will be compelled to make changes, but Mayor Harrell is seeking an exemption to shield up to a quarter of single family zones from the changes, opting for triplex zoning in those areas instead. State lawmakers who spearheaded the move including Olympia Rep. Jessica Bateman and Seattle Rep. Julia Reed have criticized this bare minimum approach and suggested it may not comply with the law. Ultimately, though, it may take allowing denser housing like small apartment buildings to spur homebuilding in single family areas.

An overwhelming body of evidence is pointing Seattle toward embracing housing growth across all neighborhoods in order to improve housing outcomes for everybody, but especially the Black residents that are being pushed out. OPCD’s analysis has found this time and again. The census data suggests keeping single family zoning would only exacerbate displacement given the dramatic loss of Black residents in single family neighborhoods since 1990. Meanwhile, polls repeatedly have confirmed that boosting housing options in every neighborhood would be wildly popular.

The lane has never been more wide open for this slam dunk policy move, which makes the Harrell Administration’s decision to pass the ball all the more head-scratching.

Correction: Due to a tabulation mistake, the original version of this article stated that areas outside of urban villages or single family neighborhoods saw their Black population decline by 9,126 residents. The correct number according to OPCD figures is a slightly smaller decline of 8,575 Black residents. We apologize for the error.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrianizing streets, blanketing the city in bus lanes, and unleashing a mass timber building spree to end the affordable housing shortage and avert our coming climate catastrophe. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in East Fremont and loves to explore the city on his bike.