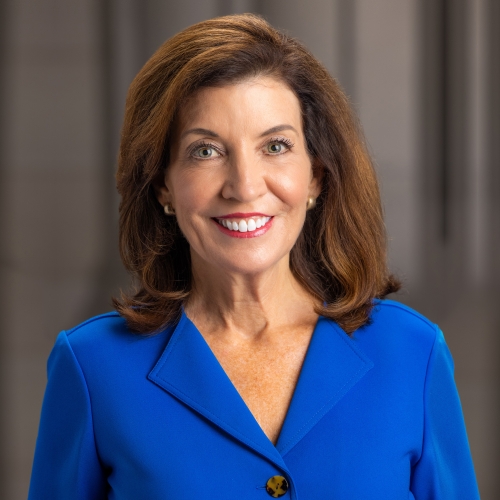

New York City had been all geared up to become the first American city to implement congestion pricing later this month until Governor Kathy Hochul announced a stunning reversal, saying she intended to shelve the program on Wednesday. Congestion fee revenue had been set to fund key projects to improve the subway system, and abandoning implementation would blow a $15 billion hole in the budget of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA).

As governor, Hochul has the power to nominate a plurality of members to the MTA board, but it would take a vote of the board to confirm her decision. The specter of a huge budget hole presented an obstacle to winning that support, so Hochul floated hiking payroll taxes on New York City businesses to partially replace funding. However, the New York State Legislature rejected that idea, facing considerable pushback from transit riders — not to mention businesses abruptly being targeted.

Riders Alliance, a New York City-based transit advocacy group, rallied riders to contact their legislators. Transit riders are holding out hope that the MTA board and the state transportation commissioner will overrule Hochul and implement congestion pricing as planned.

“Legislators must not compound Governor Hochul’s betrayal of millions of public transit riders,” said Betsy Plum, who is executive director of Riders Alliance, in a statement. “The proposal on the table will not fix the subway. A billion dollar IOU is not nearly enough money nor is it nearly secure enough to build trust and rebuild our critical infrastructure.”

Transit supporters pointed out the move risks a death spiral for the subway and climate action in the name of coddling wealthy suburbanite car commuters.

“It is simply not credible that New York has money lying around to keep subsidizing the commutes of wealthy suburbanites,” Plum said. “Killing congestion pricing narrows our options to save the subway and prepare it for climate change, risking again the death spiral we barely avoided from the pandemic.”

This isn’t just an NYC fail, this is a national fail. Seattle & cities across the country look to NYC to be a transit leader.

— Kirk Hovenkotter (@khoven) June 5, 2024

If you care about transit , take up @RidersAlliance action & keep congestion pricing moving forward. https://t.co/vp9ehzCD8O

New York’s continued waffling on congestion fees, referred to as decongestion pricing by some supporters, also could set the policy back nationally. Kirk Hovenkotter, executive director of Seattle-based Transportation Choices Coalition, stressed the national importance of New York staying the course.

“Congestion pricing is not just a NYC story,” Hovenkotter told The Urbanist. “It’s a national story. Places across the country look to New York City for leadership. Like New York, we have a looming funding gap, and the urgent need to redesign our most dangerous roads and fully fund the transit that riders deserve.”

Transportation Choices Coalition has advocated for road pricing as a means to fund transit and safety improvements and drive down carbon emissions, alongside other transit leaders and climate groups.

In 2018, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan announced her intent to pursue decongestion tolling in the downtown core and secured a $1 million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies for that purpose, but ultimately all that resulted from the half-hearted push was a study that sat on a shelf. Advocates had hoped New York City taking the plunge could jumpstart some momentum on the stalled policy in Seattle.

Tolling has also been a stumbling block in Oregon, where tolling revenue had been intended to fund highway improvements in the Portland metro before Governor Tina Kotek pulled the plug this spring. Oregon had spent seven years and $61 million planning the toll system. Continued opposition to tolling could jeopardize the $7 billion and counting I-5 Interstate Bridge Replacement project over the Columbia River.

“Congestion pricing offered inspiration (and a prime case study) for our state and region to look at progressive revenue strategies that encourage transit and cut greenhouse gas emissions,” Hovenkotter said. “Governor Hochul’s decision sets back those efforts.”

Transit funding & decongestion policy are paramount climate issues. @GovKathyHochul should resign as co-chair of the @USClimate Alliance if she does not change course on decongestion pricing for New York. https://t.co/jm3PsKhSHl

— Joe Fitzgibbon (@joefitzgibbon) June 7, 2024

Rep. Joe Fitzgibbon (D-West Seattle, 34th) took criticism a step farther and called on Hochul to resign as co-chair of the U.S. Climate Alliance if she does not see decongestion pricing through. Fitzgibbon was instrumental in Washington State Legislature’s successful effort to pass the Climate Commitment Act, a cap-and-invest carbon pricing system, in 2021.

Hochul had vowed support for decongestion pricing as recently as two weeks ago, but she seems to have become aware of “unintended consequences,” which include concerning poll numbers in suburban swing districts, in the last couple of weeks, painting herself as protecting the middle class in pausing the program.

“A $15 charge might not seem like a lot to someone who has the means but it can break the budget of a hardworking or middle class household,” Hochul said. “It puts the squeeze on the very people who make this city go.”

A study for New York City’s congestion pricing system found that the overwhelming majority of people who drive into Midtown and Lower Manhattan are rich — not the blue collar sufferers that Hochul and other congestion pricing opponents have evoked. The congestion area would only apply to people who drive into Manhattan below 60th Street, many of whom already pay bridge tolls. It would not apply to trips within or between the other boroughs. This makes it a toll paid largely by New Jersey residents and other wealthy suburbanites. Transit really is the dominant mode in moving people to and from Manhattan.

Approximately 3.9 million commuters enter into Midtown and Lower Manhattan daily, with over 75% using transit; high rates of trips are also made by walking and biking. Conversely, some 700,000 vehicles enter into Midtown and Lower Manhattan every day, according to the MTA, creating severe gridlock. The MTA projects that congestion charging will reduce this by 100,000 cars, about a 14% decrease in traffic, while moving a large share of those trips to transit.

Hochul’s statements last month at the Global Economic Summit in Ireland went in the opposite direction. “It took a long time because people fear backlash from drivers set in their ways,” she said. “But, much like with housing, if we’re serious about making cities more livable, we must get over that.”

Hochul showed that she is not over that yet, especially not with prominent Democratic political insiders and consultants in her ear. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, who represents a Brooklyn district, endorsed the move and Politico reported he has discussed suburban swing district polling ahead of the poll and stressed the importance of flipping Congressional seats in suburban New York to retaking Democratic control of the House. And of course, Hochul might have begun to fear for her own reelection prospects in 2026, if she had bought into the suburban revolt hypothesis.

MTA board members have said they were blindsided by Hochul’s proposal, leaving them scrambling to adjust capital investment plans. Behind the scenes, they’ve asked if Hochul intends to cancel the Second Avenue subway extension into Harlem or gut the agency’s accessibility program, Curbed reported. As a legacy system built before the Americans With Disabilities Act, New York’s subway has many stations that are hard or impossible to reach for disabled people and for families with small children.

New York City Mayor Eric Adams, who had previously sought to distance himself from pricing, has supported the move to pause the program.

“If she’s looking at analyzing what other ways we can do it and how we do it correctly, I’m all for it,” Adams said. “We have to get it right. This is a major shift in our city and it must be done correctly.”

Whether Hochul and Adams will ever get the political backbone to embrace decongestion pricing remains to be seen. A pause would give them a chance to summon their resolve, but otherwise accomplishes nothing.

The political calculation that pausing decongestion pricing would score points with suburbanites also appears to be tempered by the fact the state has already invested hundreds of millions in infrastructure to implement the program. This last-minute reversal makes New York Democrats appear fickle and fiscally irresponsible, which could be a bigger political liability than simply choosing transit and the environment over wealthy motorists who want to drive into Lower Manhattan.

Decongestion pricing has a proven track record in lowering pollution, asthma rates, and traffic crashes while lessening traffic jams and funding infrastructure improvements. Past experience in cities like Stockholm that have implemented decongestion pricing shows that seeing is believing, and public support swings dramatically once those benefits are on display. American cities are never going to get a chance to see for themselves if they never take the leap.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrianizing streets, blanketing the city in bus lanes, and unleashing a mass timber building spree to end the affordable housing shortage and avert our coming climate catastrophe. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in East Fremont and loves to explore the city on his bike.