The Sound Transit Board was scheduled to vote on betterments policy reform today, limiting local jurisdictions’ ability to foist costs on the agency.

Sound Transit serves 53 separate jurisdictions across the Puget Sound region, and each one has a different approach to permitting to bring transit projects and the surrounding station area improvements to fruition. This creates a bureaucratic quagmire for agency staff to navigate that has contributed to the agency’s struggles to contain costs, scope, and timelines on projects for many years. Today, the Sound Transit board had been set to vote on policy that seeks to iron out some of those kinks, but ended up tabling the motion for a later meeting.

Last year, the Sound Transit board’s Technical Advisory Group (TAG) — a group of top infrastructure experts hired by the agency to give advice — issued a report flagging the issue and urging action to reform the agency’s “betterment” policies. By doing this, the agency could, in theory, reduce project complexity, time, and ultimately costs.

“Unlike [the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT)], [Sound Transit] does not have commensurate legislative authority to execute projects and therefore must negotiate its way through the 53 jurisdictions it serves,” the TAG report states. “[Sound Transit] does not have the responsibility, nor should it feel the obligation to build whatever is requested of it by those jurisdictions.”

The TAG is not saying that Sound Transit should not provide any betterments as part of projects, but they are making the case that how they are accommodated should change significantly.

“The TAG recommends creating a comprehensive betterment policy that outlines what the agency is responsible for providing as part of a capital project, including required mitigation measures, and how to address betterments requested by partner jurisdictions,” the TAG report states. “The policy should also address how to proceed when partner jurisdictions fail to work in good faith or break previously agreed-to agreements. This policy will provide staff and partner agencies with clarity on how ST will scope projects in the future.”

Past challenges with local permitting processes have led Sound Transit to try to improve outcomes by creating “partnering agreements,” where the agency essentially pays local governments years before submission of permits to staff up their permitting and planning teams to solve issues early. The TAG supports these agreements.

“In interviews, the TAG heard examples where an under-resourced municipality rejected a contractor’s construction plan because the consulting engineer for the local jurisdiction did not understand a routine WSDOT concrete standard. Resolving this misunderstanding, which consisted of educating the consulting engineer about the standard, added a 12-week delay,” the TAG report states. “In other cases, municipalities have wrongly asked ST to cover the costs of road widenings adjacent to a new right-of-way, pay exorbitant mitigation costs to get permits to shut down traffic lanes and roadways, or use more expensive materials than required by code.”

The latter example is why the TAG also wants Sound Transit to update its construction standards documents for stations and common project elements, unifying standards across agency projects and creating a source of authority to point to when local governments choose to weigh in on project design.

Over the past few months, the Sound Transit board’s executive and system expansion committees have been deliberating on potential policy changes for betterments. This would involve consolidating three policies (Scope Control Policy, Permitting Activities Policy, and Reimbursement Policy) into one policy document and revising how they operate.

Alex Krieg, a Sound Transit planner, briefed the board’s Executive Committee on key elements of the proposal earlier this month.

“We’re […] carrying forward the requirement from the existing Scope Control Policy that project betterments must be paid for by the requesting party. And while we will make every effort to incorporate a project betterment that a requesting party is paying for, we may also decline to do so if it jeopardizes our ability to deliver the baseline scope,” Krieg said. “This is all generally straightforward when Sound Transit and our partners agree about an element being a project betterment. The challenge and the issue identified by the TAG is when there is a difference in interpretation about whether an element should be part of the project or should be a betterment.”

Agency staff have also highlighted that jockeying over betterments without clear expectations can sour relations between the agency and its local partners.

“This challenge is exacerbated when [a jurisdiction] seeks to impose the inclusion of a project element through the regulatory process, which is typically resisted by a project team and can create a circumstance where partners become adversaries, disputes arise and fester, and time — and sometimes a lot of time — is spent trying to resolve these disputes,” Krieg said.

The proposed policy would better define what a betterment is, project scope definition, and establish a dispute resolution process for out-of-scope requests foisted upon the agency by local governments through permitting and regulatory processes.

Simply put, a betterment is “[a] project element beyond required scope to plan, build, and operate the regional transit system.” Under the proposed policy, Sound Transit would not be obligated to incorporate betterments if the agency “determines there is a potential risk to the project schedule and/or budget associated with the project betterment request.” Sound Transit would still attempt to make reasonable efforts to include betterments, but a requesting party would be expected to pay for an appropriate share of associated costs.

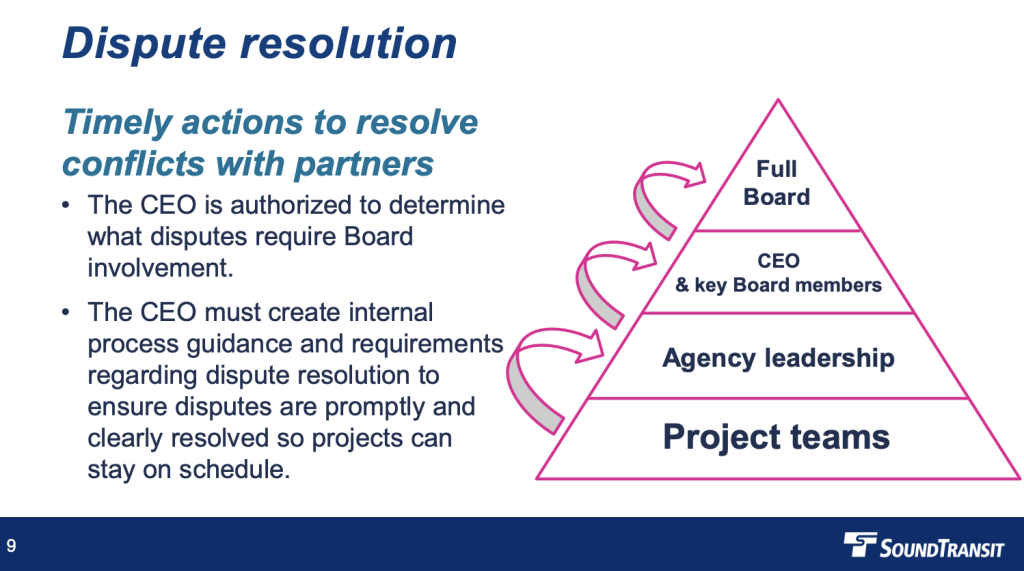

When local governments attempt to extract out-of-scope betterments on Sound Transit, the proposed policy would direct agency staff to commence an informal dispute resolution process. The process would require agency project teams to elevate a dispute internally, which could include higher agency leadership, the Sound Transit CEO and key boardmembers, or even the full agency board to resolve. What the exact process will look like has yet to be fully worked out, however.

Current agency policy and process lets Sound Transit capitulate to betterments requests even if they go against the policy intent. This pushes the extra cost onto subareas benefiting from the betterment, though federal dollars can’t be used for such betterments.

A stronger process of review could put the brakes on excessive requests. However, several boardmembers are proposing amendments to water down the betterment policy proposal.

Auburn Mayor Nancy Backus is sponsoring most of the amendments, some of which would substantively alter the policy and give local governments strong permitting authority to extract betterments. At the May Executive Committee meeting, Mayor Backus pushed back against staff urging expedited resolution to conflicts with local governments. She said that she wants Sound Transit to be good partners instead of being “seen as bullies,” even if that means requiring more of Sound Transit, which she claimed is “doing what voters asked us to do as well.”

One of Mayor Backus’ amendments would fully strike a provision providing for a dispute resolution process when local governments step over the line for project scope through permitting conditions.

In numerous other amendments proposed by Mayor Backus, language would be added to require Sound Transit to meet any local regulations and standards as a way to force the agency to construct improvements that it wouldn’t ordinarily consider part of project scope. Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell has his own suite of amendments that would largely achieve the same effect as the Backus amendments.

At the May meeting, WSDOT Secretary Roger Millar also voiced some concern about the betterments policy.

“[WSDOT has] a safety oversight responsibility per federal law that I don’t think should be subject to a betterments policy. And we also have a lease or lessee-relation that I need to address state requirements there,” Millar said. “And I really don’t see that as a discussion of betterments about what Sound Transit’s operating and maintenance responsibilities would be as a lessee of upstate property.”

To resolve those concerns, Millar is sponsoring an amendment that would add intent language to the policy, but not to the official policy. “Sound Transit constructs its projects to comply with all federal, state, and local regulations and standards and to ensure that partner agencies can continue to operate and maintain their property and infrastructure that interfaces with Sound Transit projects in a safe and efficient manner,” Millar’s amendment reads.

The amendments may seem relatively innocuous at first blush, but the impact could be significant, as it gives further authority back to local governments to adopt new requirements and procedures under the guise of permitting processes. Local governments have a way of building very unwieldy systems to extract concessions out of third-parties, which can include:

- Discretionary conditional use permits;

- Design guidelines and design review bodies;

- Special review district bodies;

- City council and planning commission involvement; and

- Building highly extractive development regulations applicable only to transit.

Codified though they may be, this is exactly the kind of local government abuses that the TAG would like to constrain by updating betterment policies so that Sound Transit doesn’t bow to unreasonable demands. Providing such a loophole could defeat the original purpose of the policy.

In the longer term, however, changes to state law to treat Sound Transit more like WSDOT might offer the best hope of the relief that Sound Transit is seeking. The TAG recommendations included several examples of transit and public agencies that have much more control over their projects, with special attention given to Greater Toronto’s transit agency.

“MetroLinx in Ontario has master permitting authority within 50-feet of its approved right-of- way, which shifts the permitting responsibility from jurisdictions to Metrolinx,” the TAG report states. MetroLinx, which operates in the Toronto area, is therefore able to plan and construct projects in a much more streamlined manner. The agency is currently undergoing a massive expansion of its GO Transit regional and commuter rail system.

Conversely, the essential public facilities statute in the state Growth Management Act is fairly toothless since it primarily requires local governments to have processes and regulations in place to permit such facilities. The statute doesn’t set specific parameters around how processes and regulations must be reasonable to a project scope and effort to site an essential public facility. This allows local governments to, on paper, comply with the statute, and then exert enormous power over permittees wanting to site their projects in their communities.

Adopting a revised betterment policy in the interim will certainly address some of Sound Transit’s project development and cost challenges, but amendments could water it down. Even if those amendments are rejected, more comprehensive construction standards and tighter betterment policies alone won’t be sufficient to fully control costs and project timelines in the long-term. Along with tighter internal practices and steadier alignment decisions, it could take new state-granted powers to have more direct control over its projects for Sound Transit to truly be a leader in cost control and project delivery efficiency.

Sound Transit 3 is an ambitious transit expansion program of utmost importance to the region, one with many downstream impacts on housing, land use, and transportation policy. Spending billions of dollars more than necessary on projects not only slows the agency down on project delivery, but also hinders it from delivering future transit expansions. Until the board zeroes in on delivering high quality transit to riders rather than doling out ancillary benefits to local stakeholders, issues with cost control and delays are likely to persist.

Update: The Sound Transit Board tabled the betterments policy item at Thursday’s meeting, delaying the vote.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrianizing streets, blanketing the city in bus lanes, and unleashing a mass timber building spree to end the affordable housing shortage and avert our coming climate catastrophe. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in East Fremont and loves to explore the city on his bike.