In the United States, around 54 million people were food insecure and 23.5 million lived in food deserts in 2022, according to the USDA. In some parts of Washington state, nearly 20% of people were food insecure. While the U.S. has the largest economy in the world and plenty of resources, access to food is not equal. Food deserts disproportionately affect urban communities, and are also racially distributed, with Black communities the most affected by food deserts and food insecurity.

Urban agriculture is one way to respond to this issue. By making use of parks, green spaces between buildings or in public areas, as well as private land such as rooftops or indoor environments, communities can grow food and sell or give this to others. Urban agriculture might look quite different from place to place.

In some areas, it might involve the use of large areas of unused or abandoned land or buildings to grow fruit and vegetables, while in other places gardens may be established primarily on rooftops or on balconies. Some farms produce a wide variety of low-cost or free produce for the purposes of food banks and community needs, while other growing operations might be focused on edible flowers and micro-greens, which are then sold at local restaurants.

What is urban agriculture?

From community gardens to urban farming, permaculture and green roofs, a lot of different terms are connected to the idea of urban agriculture. But as for what urban agriculture is, the definition can vary from quite broad, to very specific. Melissa Spear, the Executive Director at Tilth Alliance, a non-profit organization working to create equitable food systems in Washington, defines urban agriculture as simply “any activity that is growing food within a densely populated area. It doesn’t even necessarily have to be a city. It can also be a small town, or anything that’s not defined as rural.”

The difference between urban gardening and urban agriculture can also be one of scale: Dr. Sabine O’Hara, a professor at the University of the District of Columbia, explained that urban gardening is also a term often used for non-commercial activities, while urban farming or agriculture is a term that applies more to organizations who make above a certain earnings level from what they grow. The term “agriculture” tends to be used for larger activities, while “gardening” implies smaller communities or areas of land.

In all cases, a wide variety of plants can be grown in urban areas, particularly those that have shallow root systems, such as leafy greens, capsicums, tomatoes, herbs, and edible flowers. O’Hara notes that for many urban agriculture operations it can be crucial to have a mixture of high-earning and high-nutrient crops, so that the garden remains financially viable in the long run, as well as being able to serve the surrounding community.

What are the benefits of urban agriculture?

One of the main benefits of urban agriculture is that food is produced locally, allowing people in urban areas a higher level of food security and self-sufficiency. O’Hara said that for many urban populations, “it’s not only about food security and food access, but rather nutrition security and nutrition access. Not all food is created equal. How much access do we get to vitamins and unprocessed food, to fresh leafy greens that make a real difference in the dietary needs of people?”

Urban agriculture is one way to bring these nutrient-dense foods closer to the communities who need them and to make those foods more accessible.

Urban gardening can also foster community, and encourage people to connect with others in their neighborhood. Shared gardening activities, investment in a collective project, and gatherings that arise as a result of urban garden events can all help people to make connections in the city. The mental health benefits of community interaction have also been touted by researchers as one way of combating the “loneliness epidemic” that many urban areas are facing.

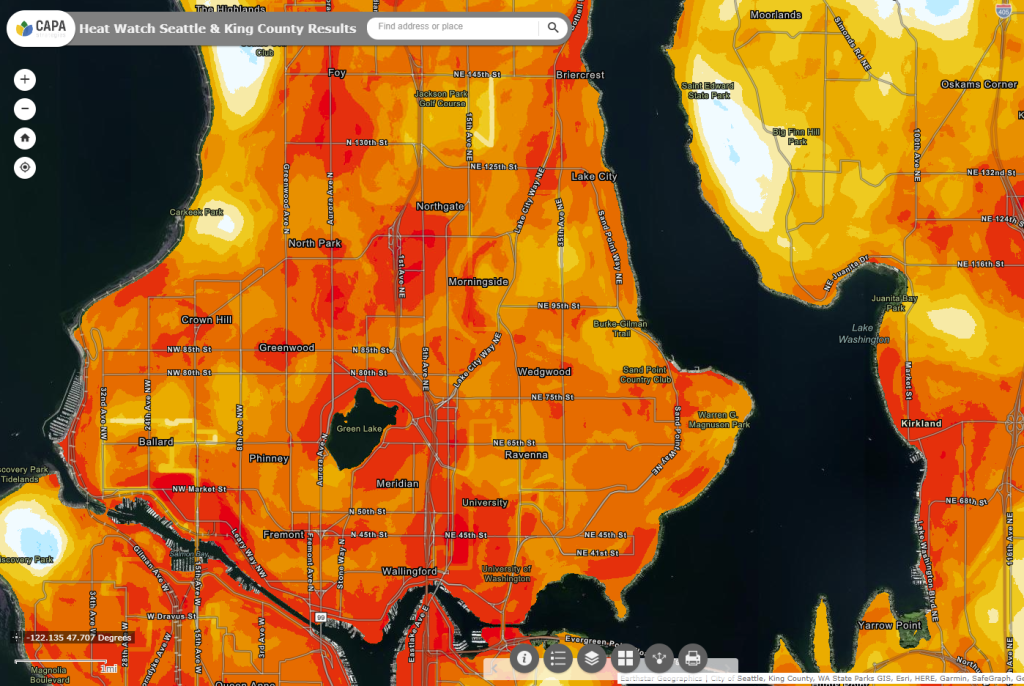

In addition, the use and maintenance of green spaces for urban farming also contributes to permeable surfaces in the city. These surfaces can absorb water during times of rainfall, and release the moisture later (a concept known as a “sponge city” when applied widely across the urban space), and can help to reduce the urban heat island effect.

What are the challenges of urban agriculture?

O’Hara said it directly: “In urban agriculture, one of the biggest challenges is access to land and access to sufficient land.” Formal access to land can be made complicated with long or difficult procedures, and informal use of land risks resources and effort being removed or destroyed. In addition, land is often prohibitively expensive for people to purchase, and even more so in dense, urban spaces. Zoning rules also make particular areas completely off limits for certain activities, further complicating the access issue, but ways to overcome the obstacles exist.

“There are some ways of farming that require very, very little land, if you farm not in soil, but hydroponically or aquaponically,” O’Hara said. “This is what’s called ‘controlled environment agriculture,’ and then you actually don’t need a lot of land, and then the business models are really interesting.”

This can include the use of greenhouses (for example, set up in abandoned buildings), basements, and other indoor spaces.

Spear also emphasized that regardless of which type of land or building is used, maintaining access to that land or building can also be a challenge, pointing to an example to illustrate the point.

“In Seattle, there was a BIPOC-led farm which was on church property,” Spear said. “They had been there and invested a lot of sweat equity into developing this small urban farm, but they [only] had a five-year lease. And then the lease was up, and the church was like, ‘Nope, we want to take over the space now,’ and that’s really rough. Having long-term access to land within urban centers is really tricky.”

Furthermore, water access can also be difficult. City water can be used, but in urban areas with high water prices and low access to water, gardens can’t always establish the access they need year-round. Spear ran into this issue back when she was working in Connecticut.

“We really worked hard in New Haven to get the city to provide water to community gardens at either a reduced rate or for free, and to actually put in spigots that didn’t freeze in the winter,” Spear said. “Connecticut gets really cold. So, [they needed] to put in a particular type of water spigot, that wouldn’t freeze in the winter, so that the community garden every year wouldn’t have to turn the water off in the winter.”

An additional challenge is something that arises with almost any kind of urban development: Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) activism. Spear said that when they set up their Rainier Beach Urban Farm project, some people in the neighbourhood didn’t want it.

“People were complaining, saying ‘you can’t put this here, this is terrible,’ but once you’re actually there, and people see the activities there, they [realize] there’s nothing scary or bad going on,” Spear said. “[Now] every time we have an event and I’m there, there are always people who are like, ‘I live right down the street and I had no idea!’ … but it takes a long time.”

Despite the challenges, numerous urban farms have established themselves both in Seattle and elsewhere, to meet the needs for food security of their local communities.

Beacon Food Forest, Seattle

One great example of urban agriculture in Seattle is Beacon Food Forest. Set up in agreement with the City of Seattle Department of Public Utilities, they have a number of key values that they hope to enact through their project.

As Khalil I. Griffith, Site & Programs Director at Beacon Food Forest, said one of their main goals is to “alleviate a lot of that pressure that has been placed on us” in relation to food and nutrient access, especially for people in low income areas, such as those surrounding the Beacon Food Forest area.

“Especially now, I think it’s harder and harder for people to be able to afford produce, so we have this fresh food for people and they can come and take what they need or take what they want,” Griffith said.

Beacon Food Forest offers growing spaces that people can harvest and forage food from, P-Patches (small plots of land available for gardeners to plant in), educational events and community gatherings, and donates food to local food banks.

Signage at Beacon Food Forest is offered in five languages. “We have a big population [in this area], where folks are mostly either first or second generation immigrants and their native language is not English,” Griffith said. Language barriers are also a challenge that was noted also by other urban agriculture organizations such as Tilth Alliance (below).

Spear said that immigrants to the area are “often the ones who really start to recognize the value of urban agriculture and they will start their own small agricultural operations. And they are focused on culturally relevant foods,” so that their communities can improve food access and cook familiar meals. When other community gardens are established, including multilingual signage and planting culturally-relevant foods can help to ensure that immigrant communities are also able to access these spaces.

Tilth Alliance, Seattle

Another project working with urban agriculture in Seattle is the Tilth Alliance. Tilth Alliance has helped to set up a number of gardens in Seattle, including the Bradner Gardens Park, Good Shepherd Center, McAuliffe Park, and Rainier Beach Urban Farm & Wetlands. This urban farm and wetlands is Seattle’s largest urban farm.

The Alliance provides a number of programs both managing community gardens and urban farms in Seattle, as well as offering educational events, training, outreach programs, cooking programs, and other services. They also actively try to encourage diversity in their community, and provide support for people in marginalized groups, such as the elderly.

“We have a very robust senior meal program, centred around the East African community in Seattle, which is a very large immigrant community. That meal program cooks their meals twice a week at Rainier Beach Urban Farm,” Spear said. “It’s grown to be around a hundred seniors that come to the site.” In addition, they offer a culturally relevant plant start program, in which horticultural experts work out what’s missing in terms of the crop offering for local communities, and what immigrant groups are looking for.

Prinzessinnengärten, Berlin

Urban gardens and farms are an international phenomenon. One such garden in Berlin began as a pilot in 2009, the Prinzessinnengärten (Princess gardens). The site on which the garden was built had been “a wasteland for over half a century” — one example of transforming an abandoned space into a community garden.

The garden now grows organic herbs and vegetables in raised beds made from recycled Tetra Paks, rice sacks, and crates, and transforms additional unused or abandoned urban places (such as building sites, car parks, and roofs) into green meeting spaces and farmland. The entire Prinzessinnengärten was designed to be portable if necessary — a feature that was eventually needed in 2020, when the garden moved from Moritzplatz to the site of the former Neuer St. Jacobi cemetery.

The garden’s primary goal is to provide educational and community opportunities, including planting, growing and harvesting, beekeeping, making compost, and learning about participatory urban development.

Looking ahead

As for what’s next on the horizon for urban agriculture, both Beacon Food Forest and Tilth Alliance have specific goals for their farms, as well as for the movement more broadly.

Griffith said that their next plan is to make Beacon Food Forest more accessible, as he explains “accessibility could have been thought about more [from the beginning] but other priorities were getting us space established, having a place for food.” Now, they want to improve access to the garden “in our neighborhood, where we have a lot of other folks with mobility access issues. … They need [the garden] just as much as we do.”

Even more so, Griffith hopes that by improving accessibility, they will improve the diversity of the community within the garden itself: “A big part of [our goal] is diversity. … You know the more diverse the voices are in the room, the better chances you have of ensuring that all the boxes are checked. There’s somebody there to be like well, hold on guys.” This can help to ensure that the project continues to develop in a welcoming, diverse, community-focused way that caters to everyone’s needs.

Tilth Alliance also has more plans to sustain and expand the food access components of their work. In particular, they offer a farm stand at which people can claim $20 worth of free produce. The food sourced for the farm stand is also only procured from small, hyper-local, organic, and primarily immigrant farms. In addition, a new initiative they are expanding into is seed saving, with a particular focus on culturally-relevant foods for their community, and organic seeds.

“We are now creating seed libraries where people can share seeds that they’ve saved,” Spear said. “Within the urban context that’s actually very important, in particular, when you’re trying to preserve the biodiversity of food that is being grown in urban centers.”

Urban gardening and the “buy local” movement is also becoming more popular. “When food is grown at a far distance from where it is consumed, then you also need a coal chain, right?” O’Hara said. “So there is a huge carbon footprint associated with that.”

With increasing concerns about climate change and transport emissions, buying locally and supporting urban farms and community gardens has become increasingly common for restaurants, cafes, and events. O’Hara also notes the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, which, she said “really taught us a lesson or two about the vulnerability of supply chains.”

In addition, when some fruits and vegetables are easily perishable, such as lettuce, spinach, and other greens, it makes practical sense for communities to buy these locally instead of transporting them in. As urban agriculture becomes more established, communities and businesses are able to more easily make the “buy local” choice.

But Spear said that the core of urban agriculture is much more than just growing food: “The food may come out of the farm, but it’s more about the whole process of growing, harvesting, and eating together in communities. There are so many benefits: there are health benefits, both physical health and mental health benefits, there’s social benefits, there’s just enjoying a good meal. The feeling of putting a seed in the ground, watching it grow, harvesting a tomato, and eating it. There’s nothing like it. You can say: ‘I did this, I grew this amazing tomato’, and I think that that’s kind of at the heart of it actually.”

Leah Hudson is an editor and writer published by Insider, Atlas Obscura, and Penguin Random House New Zealand. Leah loves to write about sustainable urban development, mental health, and matters of the heart. She spends her time reading, walking her dog, and eating unreasonable amounts of chocolate. You can find her at https://leahhudsonleva.com/.