Article Note: This is the first of two pieces by Alex Brennan on the Seattle 2035 growth alternatives. Next week, he’ll share his vision for an Alternative 5. You can read the second part in full here.

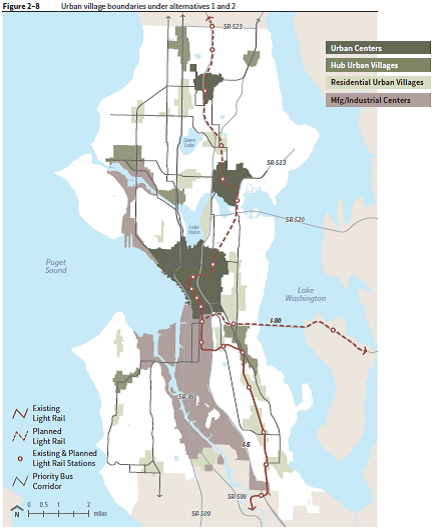

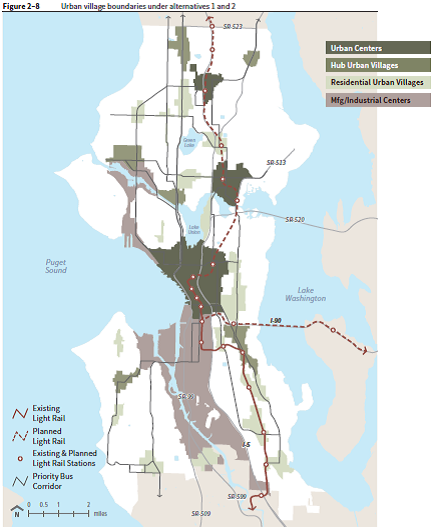

Determining where and how we want our city to accommodate future growth is the central purpose of the comprehensive plan process mandated by the State as part of the Growth Management Act. The state develops population and employment growth projections that are passed down through the regional councils and eventually end up allocated to specific cities. Those cities then have to decide where the growth they have been allocated should go within the city. In 1994, Seattle created its first comprehensive plan, which identified “Urban Villages,” places within the city where growth should be directed. The plan gets a major update every 10 years (we are a little late this time). Seattle has grown and changed a lot since 1994, but our Urban Village boundaries remain essentially the same. When you are in the urban villages surrounded by construction cranes and streets closed for construction it is easy to forget that, in most of the city, the vast majority located outside of the urban villages, there is almost no construction or physical change at all. That massive disparity is thanks to the Comprehensive Plan and the zoning and neighborhood plans that flow from it.

If we want to be an affordable city, a racially equitable city, an environmentally sustainable city, and a great place to live, getting the comprehensive plan right is really important. Seattle is at a critical juncture in the comprehensive plan update process. The City has released four alternative growth scenarios as part of the draft environmental impact statement. Until June 18, you can give input on which alternative you think is best or if you think the existing alternatives do not represent the best way to meet city goals and a new option needs to be added. I’m going to argue the latter.

These plans come with a lot of aspirational language about all sorts of things, but it’s important to focus on the real power of the plan, the location of population and employment growth. There are two main variables to look at. The first is should we grow a little bit in a lot of places or a lot in just a few places? The second is where within the city should those places be? Let’s take them one at a time and then together.

Should we grow a little bit in a lot of places or a lot in just a few places?

The gut urbanist response to this question is often that we should concentrate growth in fewer places. Growing a little bit in a lot of places sounds like sprawl. Growing a lot in a few places sounds like the kind of compact development that is associated with walking, transit, and a complete community. That’s true at the regional scale, when dispersal means new car-dependent suburbs replacing farms and forests, but not when allocating growth within a central city.

All of Seattle has the potential to be a compact complete community. If you concentrate growth in just a few neighborhoods either you get the wholesale redevelopment of that neighborhood, essentially a market based version of 1950’s urban renewal, or you get highrise (over 70 feet tall) buildings that for safety reasons must be built in an expensive way (or you get both like in South Lake Union). It can be hard for the people and culture of a neighborhood to make it through overly concentrated growth. I see this in the residents and small businesses in Pike/Pine that have been sandwiched between multiple construction projects with sidewalks closed on all sides, trucks and construction noise blaring for most of the day. Spreading growth out more, on the other hand, allows neighborhoods to change more gradually, use a mix of lower cost building types, and, in many cases, build up the critical mass to become a complete community with basic goods and services, community gathering spaces, jobs, and homes all nearby.

The high cost of highrise construction is really important for thinking about affordability, displacement and who can live in Seattle. RSMeans, a construction cost data provider, offers some rough estimates online for cost comparison. Building the first 5 stories (RSMeans says 3, but as far as I can tell they are referring to type 5 construction which in Seattle you can build up to 4 stories on its own and 5 stories on top of 1 or 2 stories of more expensive type 1 construction) costs between $146 and $159 per square foot. The next two stories inch up a little bit $160 to $175 per square foot. After that it jumps to between $196 and $214 per square foot and when you get above 7 stories you have to switch construction types for everything, so the first 7 stories go up to $196 to $214 per square foot along with the higher stories (though again it’s a little unclear if this is already factored into the added cost).

Construction costs vary by site and are only one part of housing costs. Land costs (among the many additional costs) also play an important role. The benefit of building higher is that you have less land cost per square foot of construction. Cities like Vancouver, BC are expensive in part because they combine single family neighborhoods that have high land costs per square foot with highrise neighborhoods that have high construction costs per square foot.

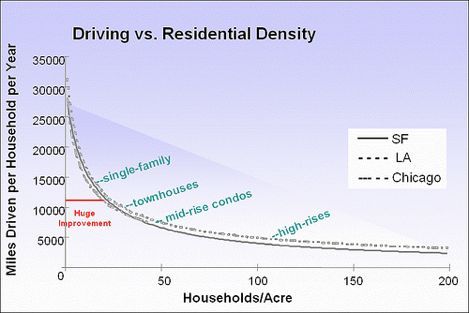

This decision about the concentration of growth also has environmental implications. Making low density single family neighborhoods in Seattle a little denser has a much bigger benefit to walking, biking, and transit than making mid-rise neighborhoods become even denser highrise neighborhoods. This is born out in countless studies whether they look within cities like this one:

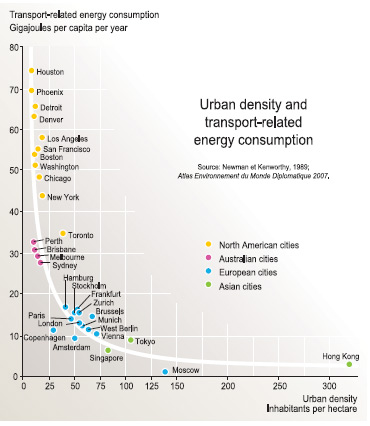

Or compare different metropolitan areas like this one:

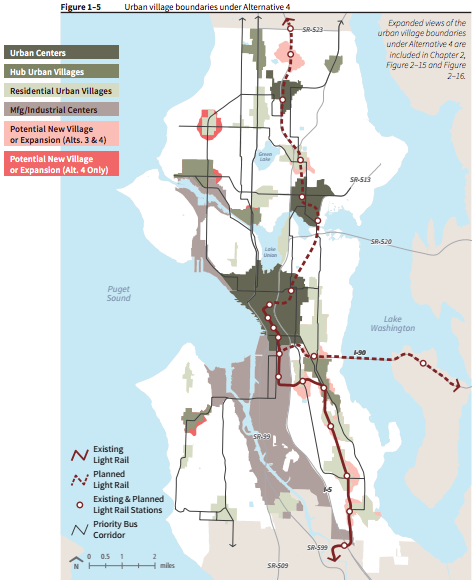

The comprehensive plan DEIS alternatives offer a range of options between continuing to grow in the same limited area we have been growing in since 1994, Alternative 1, even more concentrated growth, Alternative 2, or more dispersed growth, Alternative 3 and especially Alternative 4 (see Figure 2). In regards to the issue of concentration or dispersal, Alternative 4 is the clear winner and Alternative 2 is the terrifying loser. If you take away anything from this post, it’s that Alternative 2 is bad, really bad.

Many residents do not want their neighborhoods to change, especially single family homeowners in middle class and wealthy neighborhoods (more on that in the next post). Constraining growth to our current urban villages has only made the option of becoming an urban village appear more overwhelming as more and more growth is squeezed into the same limited area. Thus, the longer we wait to expand the urban village boundaries, the harder it is to do politically.

For these reasons I am proud that the planning department (with, I can only assume, the support of the Mayor and City Council) took the politically difficult step of including expanded urban village boundaries in not just one, but two, of the four alternatives released a few weeks ago.

Where should we grow?

Even if growth becomes more spread out, it is still likely to be focused to some extent. Should it be focused around certain criteria? The current proposed Alternatives identify two primary criteria, equity and proximity to recent transit investments. Unfortunately, these two pieces of criteria conflict. Proximity to transit investment (in this context!) is a flawed metric, bad for equity and bad for the environment. First, here is some background on the equity analysis.

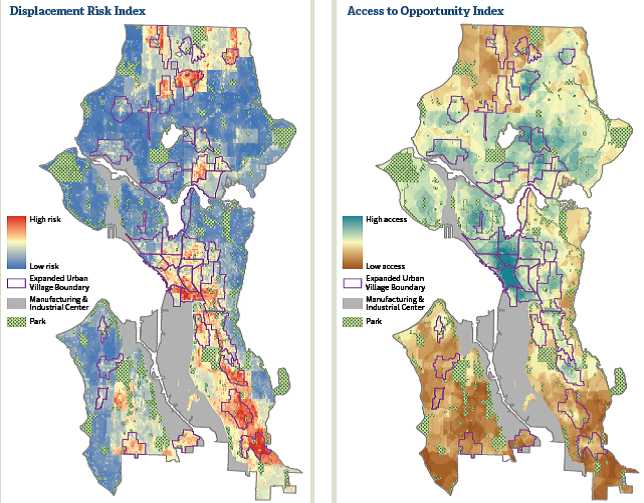

The planning department has conducted a terrific equity analysis that provides data and maps on displacement risk and access to opportunity. The City Council recently identified equity as a major guiding principle for the update. Despite the date of the linked announcement, it was not meant as an April Fools joke, but the equity analysis shows the limitations of the Alternatives currently on the table.

In Alternative 3 all of the areas suggested for urban village expansion, with the exception of a small slice of Roosevelt, also have high risk of displacement. Alternative 4 is better, it adds expansions in some lower displacement risk areas like Ballard and West Seattle as well, but the expansions are still concentrated in the high displacement risk areas. While the calculations for displacement risk and access to opportunity are complex, they essentially show us where poor people and people of color live and where wealthy people and white people live. While transit access does not have to be correlated with neighborhood wealth and race, in practice it usually is.

People of color, and even more so poor people, are more likely to use transit, so they are more likely to live in neighborhoods well served by transit. Transit agencies want good ridership and are therefore more likely, all else being equal, to locate new transit investments in poor neighborhoods. This is especially true if we are thinking about low density neighborhoods, the neighborhoods not already part of an urban village. Therefore, the only low density neighborhoods likely to have good ridership are almost inherently going to have a high displacement risk. When Sound Transit decided to locate its first light rail segment through the Rainier Valley, it reinforced this bias, exacerbating the displacement risk of Alternatives 3 and 4.

Viewed through this lens, the decision to consider expanding urban villages near recent transit investments, and only near those investments, could contribute to furthering displacement. Alternatives 3 and 4 suggest that the poor should be the ones to deal with the discomfort of growth. They also focus development in the areas with the cheapest existing housing stock contributing to a more rapid erosion of that stock. This is not a new decision for Seattle or the US.

It is easy to forget now that South Lake Union was one of the poorest (and most affordable) neighborhoods in the city before Vulcan and Amazon were given the zoning capacity to transform it. Yesler Terrace, and the preceding public housing redevelopment projects in High Point, New Holly, and Rainier Vista, are other examples, not only of our cities decision to grow in poor neighborhoods, but of federal policy supporting that decision. Light industrial areas, and the working class jobs they provide, are also often targets, think South Lake Union again, as well as current hotspots of development in the West Seattle Junction, Pike Pine, and Stone Way which were all once centers of warehousing and light manufacturing.

The City’s equity analysis of the alternatives suggests that Alternative 2 has the least risk of displacement. As mentioned earlier, Alternative 2 takes all of the development and focuses it (even more than our current comprehensive plan) in just a few places where buildings can go very high and accommodate a lot of growth – downtown, the U District, and Northgate – the urban villages designated as “urban centers.” These areas are identified as having lower displacement risk and there are fewer total places, so the thinking goes that displacement will happen in fewer places.

The problem, as I mentioned before (and as noted in the equity analysis but I think underemphasized), is that development in these areas will be highrise development, the most expensive kind of development. If we only allow the most expensive type of new housing, in the long run will that really prevent displacement? Most people are not directly displaced by their building being torn down for new development; they are displaced by rising rents for them and the family, friends, goods, and services that make up their community. Alternative 2 is the rising rents Alternative. Underemphasizing this point is one of two critical flaws in an otherwise incredibly useful equity analysis.

The equity analysis leaves us with a choice between the lesser of two evils. We can choose Alternative 2 that keeps development and growth out of vulnerable communities, but will drive up housing prices across the city or we can choose Alternatives 3 or 4 which spread out development, but only into our most vulnerable communities.

We have a regional housing supply crisis on our hands. People want to live in walkable, centrally located neighborhoods and we have not been building enough housing for them. We have a global climate crisis worsened by rich countries and their sprawling, car dependent development patterns. We have a fiscal crisis exacerbated by the same sprawling development and its high infrastructure costs. Poor people are disproportionately hurt by these problems too. They are disproportionately hurt by not allowing growth in the central city. Stopping growth is not the answer either.

The equity analysis takes the need to accommodate growth and the bad growth Alternatives currently on the table and attempts to resolve these conflicts through mitigation measures. At this risk of simplifying the analysis, the mitigation measures focus on economic opportunity programs and anti-displacement regulatory strategies. It also mentions a strategy of “equitable access to all neighborhoods” where it argues, as I have been arguing, that growth needs to be spread out to middle class and wealthy neighborhoods to take the pressure off of poor neighborhoods. However, here we get to the second critical flaw in the analysis. The scope of the equity analysis is only to look at the four Alternatives. If we really want “equitable access to all neighborhoods,” if we really want to spread out growth enough that communities can healthily absorb that growth, especially our most vulnerable communities, then we need more space to grow, we need new urban villages in other neighborhoods, we need an Alternative 5.

What could an Alternative 5 look like? Stay tuned. That’s the subject of the next post.