Linkage Fees, proposed fees on new development to pay for affordable housing, have a lot of critics. And the critics’ arguments are probably all pretty familiar by now to those who follow housing issues in the city. But for those who don’t, a quick summary: regulations that ostensibly fund affordable housing through fees on developers act like a tax on developers who pass on that cost to renters. Taxing development increases costs for developers who pull back on the production of new units; we all scramble for fewer available apartments, bid up the rent, and make everyone involved pretty miserable. This is just Economics 101 and patently true, we’re told, so get with the program you well-meaning dolts!

I hope to offer an Economics 101, or rather, a Land Economics 101 case that Linkage Fees (and other taxes on new development like Incentive Zoning) do not diminish developers’ returns and do not diminish housing supply. In fact, they are a wealth transfer from land owners to affordable housing supply. I also hope to expand the debate around affordable housing policy, which seems locked in a developer/renter rhetoric, to include land owners and the part they play in housing regulations.

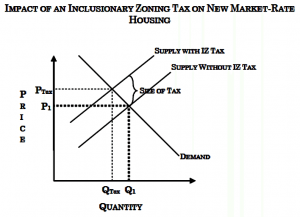

The supply-side argument casts developers as suppliers and renters as demanders. When you tax something you get less of it, goes a common refrain which also makes a lot of sense. As taxes effectively make a product more expensive, suppliers are able to sell less of the product at the old quantity; they pull back on production until they find the quantity that will be demanded at the new higher price. That’s how cigarettes, coffee, gasoline, and apartments work. Tax them, price goes up, consumption goes down, supply goes down, demand and supply wiggle around each other a bit until finally a new equilibrium is established.

From “The Economics of Inclusionary Zoning Reclaimed”:

How Effective Are Price Controls? by Powell and Stringham, 2005

When demand and supply react to changes in price, economists call those goods elastic–the more elastic a good is, the more sensitive supply and demand are to changes in prices, and the more inelastic the less sensitive supply and demand are to changes in prices. (I will focus on supply inelasticity here because it’s more important to understanding the relationship between land owners and developers.) Gasoline, for instance, typically has an inelastic supply. A 10% increase in gas prices might result in only a 2% increase in production of gasoline. Why so little? Gasoline is a hard thing to get out of the ground, transport, and refine to the point that it runs your car. It also happens to be largely controlled by cartels who don’t see much benefit in driving down prices by producing as much as demand would support at the lower original price.

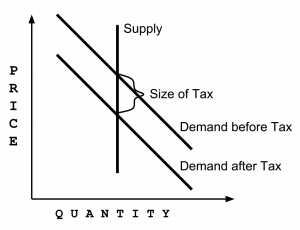

Land is like gasoline but more so. Rather than just being inelastic, it is perfectly inelastic. If the price of land goes up 10%, land supply goes up 0%. That’s just the nature of land–to be fixed in supply. Land supply is eternal… or about as eternal as it gets in economics.

The inelastic supply of land changes the supply curve from something that looks like the diagonal line above to a vertical line like below.

IMPACT OF LINKAGE FEES ON LAND PRICES

A tax on development like Linkage Fees or Incentive Zoning still “pushes the supply curve up” but because the supply curve is vertical (perfectly inelastic) instead of diagonal (elastic) quantity supplied stays the same. The demand curve for land, however, does change. It shifts down along the supply curve as the new taxes diminish potential revenue and developers pay less for the same quantity of land.

There’s a method of land valuation in real estate appraisal that states that land value is the residual of price minus potential development cost, minus the cost of borrowing money, and minus developer profit. Because of its inelasticity, land value bears the burden of changes in potential development. An important corollary to this is that when the city increases the development potential of a hot market like South Lake Union, land value again absorbs these changes minus the cost of development, borrowed money, and profit. This time, though, the result is an increase in land value.

When Linkage Fees are phased in developers will consider the revenue achievable by building an apartment, fees included, and will offer bids on land that reflect that new development reality. Because land supply is perfectly inelastic–fixed in supply–the cost of the fees will come out of the land. (In the same way a change in the zoning code comes out of or goes into the land.) And then, after developers build apartments, they will sell or rent their units based on what the market will bear. Renters and developers have an elastic relationship with each other–they change their supply and demand based on changes in prices–and abide by the familiar supply-and-demand negotiation around price and quantity.

There are possible exceptions to any theory, however. We can imagine that hill-flattening (and supply-increasing) regrades that would have been feasible no longer pencil out with post-Linkage Fees land prices, or that land owners collude to maintain prices, or that affordable run-down apartments on the verge of demolition stay that way a little bit longer. These are speculative scenarios and, although they deserve their own public airing to see which ones stand to hurt affordability, the potential benefits of Linkage Fees are very significant and grounded in the fundamentals of real estate theory and land economics.

What these theories makes clear is that by including land owners in the process of producing and supplying housing we are able to see that land owners, not developers and not renters, pay for fees on new development. Fees that go on to produce more housing supply.

Michael Goldman

Michael works as a real estate valuation analyst. He graduated from the University of Washington with a Masters in Urban Planning and a specialization in real estate. Before Serial broke the long-form true crime scene wide open, he had a podcast about pet adoption.